In honor of Black History Month and this year’s theme of “African Americans and the Arts,” we feature an excerpt from Stitching Love and Loss by Lisa Gail Collins, which captures the long history of African American quilt making through a moving account of Missouri Pettway’s cotton covering—a Gee’s Bend “utility quilt.”

In 1942 Missouri Pettway, newly suffering the loss of her husband, pieced together a quilt out of his old, worn work clothes. Nearly six decades later her daughter Arlonzia Pettway, approaching eighty at the time and a seasoned quiltmaker herself, readily recalled the cover made by her grieving mother within the small African American farming community of Gee’s Bend, Alabama. At once a story of grief, a quilt, and a community, Stitching Love and Loss connects Missouri Pettway’s cotton covering to the history of a place, its residents, and the work of mourning.

Placing this singular quilt within its historical and cultural context, Collins illuminates the perseverance and creativity of the African American women quilters in this rural Black Belt community.

Excerpt from Stitching Love and Loss

Not long after her husband Nathaniel’s passing, Missouri Pettway set out to create a quilt of his worn familiar clothes with the expressed intention “to remember him, and cover up under it for love.”1 Led by her intention to find comfort in his memory, she made her way through the steps in the quilt making practice that was her birthright. Seeking sanctuary and softness, she wound her way around this healing pattern, stitch by stitch, piece by piece, with the crown of her head bowing toward her heart. Missouri Pettway’s deliberate pursuit of this path—of this sustaining resource and practice deeply rooted within her homeplace—supported the grieving quilt maker and surviving spouse in making her way from holding the pieces of her loved one’s clothes in her hands and on her lap to being held by the precious utility quilt she conceived of them. Her quilt, as remembered, was done by design. From its initial conception, the ultimate aim for her completed covering was to cover her, to wrap it around her body and being—to remember her husband and experience their love.

At the heart of Arlonzia’s enduring memory of her mother’s quilt made in mourning lies a love story. This is absolutely no surprise; love is why we grieve. As remembered by the couple’s eldest daughter, the covering’s creation and its intended use were steeped in yearning. Following the early loss of her husband of over two decades, Missouri sought to cover her body with cloth that had recently covered his own. Clothing and cloth never again to be needed by him were now needed by her. Guided by intention and desire, she turned to a most intimate of art forms—one, like a second skin, that holds the body and moves with the breath—and created and completed her yearned-for quilt.

After Missouri Pettway completed her quilt—after the sackinglike backing had been brought around front to form and finish its edges—how might its presence and use have helped tend to her loss? Her extant textile and her daughter’s enduring testimony are silent on this matter. I would like to imaginatively consider—grounded by an understanding of grief as at once a profound experience of distress and a profound expression of love—some of the ways Missouri Pettway’s utilitarian quilt made of her late husband’s work clothes may have been of sacred utility.

Beds know grief and for good reason. While lying in bed, there is no longer the need to hold oneself up or carry one’s weight. As a result, effort lessens and loads lighten. As grief can be exhausting and heavy, this can feel like a welcome respite. Beds physically support and stabilize the body, enabling ease and inviting rest. Quilts can assist with this, too, offering a warm cradle or caress. Supported and held by her bed in this way, perhaps Missouri Pettway’s sage and simple act of pulling her cotton quilt over her body sent a soothing signal to her mind that it was now the time for a soft pause or rest. Once swathed by the sheltering cover of her quilt, perhaps its gentle heft furthered this calming, steadying effect. With all hope, she rested in this way: braced beneath by her bed and protected on top by her cover. The former supported the weight of her body; the latter supported the weight of her grief.

Lying under her quilt, with its familiar fabric touching her skin, may have felt something like a familiar embrace. And perhaps this felt sense, this experience of seeing and feeling her loved one’s well-worn and well-remembered clothes in this way, offered the quilt maker a tender path to feel his love, remember his presence, and closely carry his memory. As memory, emotion, and the sense of smell are linked and share wide-open doors, perhaps his lingering scent, alive within the warp and weft of the cloth, also offered an opening to cultivate and continue their connection.

With the sounds and silence of the night and the giving way of the light, grief can give way to a more private, solitary mourning. While under cover of the night—and a quilt—being in bed can provide a place for needed rest and desired communion, as sleep can serve as a site of reunion, a place where lost loved ones can be found. At the same time, lying in bed leaves us alone with our innermost self and our secretly whispered words, leaving us with little choice but to meet face to face our suffering and fears. For while the body is quiet and still—while it has nowhere to go and nothing to do—the mind continues to move, sometimes, distressingly, with increased intensity. When Missouri Pettway was engaged in the seemingly solitary step of piecing her quilt top, this purposeful task may have enabled the quilt maker to shift between processing and, mercifully, pausing the pain of her loss. By contrast, this protective pacing—direct reckoning with one’s shaken inner world paired with a respite from it—was probably difficult to come by while lying awake in bed within the thick grip of grief, where the only pause to pondering the enormity of her loss was likely the elusive release of a deep sleep.

Loss and longing might be felt especially acutely as one rests the body and tries to transition into sleep. For the long nights of mourning are a time when those who are grieving a loved one are pressed to confront what they are achingly coming to realize is true: someone they love is no longer here with them on earth. That come morning, they will still be in mourning. If Missouri and Nathaniel Pettway routinely shared a bed, his missing presence would have perhaps been especially potent and palpable while lying under the warm weight of her quilt of his clothes—the now empty space that had recently held his body figuring as stark evidence of his physical absence and his lingering scent serving as a direct door to memory.

Intimately associated with life and death, beds are bound with sickness, dying, and death as well as birth. Sites of healing and love as well as loss and remembrance, beds are where we often take our first breaths and sometimes our last ones. Following nearly a year of sickness and sorrow, Nathaniel Pettway likely died at home. Struggling for nearly a year with a terminal illness, he may have spent the very last part of his journey on earth in bed, as both caregiving and homegoing commonly happen here. Bound by bed and hopefully wrapped within a warm and comforting quilt, his shrouded body, likely weak and weary, readied for eternal rest. And during this extraordinarily difficult and delicate time—when life narrows to the four corners of the bed, while its meaning infinitely expands—Missouri Pettway may have sat bedside, caring for her husband, providing a reassuring presence and supporting his dying needs. Perhaps during his final hours, she, along with other family members, kept vigil posed in prayer.

The bed where Nathaniel Pettway made his transition may also have been the same one where Missouri mourned his loss. As such, it may have been both the site of his dying and his passage and a place of her mourning and remembrance. Moreover, this soft space where the husband and father was cared for before passing on and crossing over may have also been the site where the couple’s children were conceived and first breathed life. This bed—their bed—was a place of passage. On it, with all hope, Missouri lay under her quilt of Nathaniel’s clothes and fully experienced what she had expressly sought: “to remember him, and cover up under it for love.” Embraced in this way by her quilt—tucked under its protective cover—she may have tended her grief, remembering her husband, who had recently lay dying and been laid to rest, processing his long illness and early death, facing her fears for their family’s future, feeling the immensity and finality of her loss. Held and supported by the quilt of her own creation, she likely sought the strength and found the faith to make it to morning and begin a new day. And ever so slowly—at the pace of healing—moving toward the time when the memory of her beloved would feel less like pain and more like peace, sustained by the love that lies here.

Notes

- Arlonzia Pettway, quoted in John Beardsley, William Arnett, Paul Arnett, Jane Livingston, and Alvia Wardlaw, The Quilts of Gee’s Bend (Atlanta: Tinwood Books, 2002), 67. ↩︎

- Missouri Pettway, Blocks and Strips Work–Clothes Quilt, 1942, cotton, corduroy, and cotton sacking, 90 x 69 in. National Gallery of Art, Patron’s Permanent Fund and Gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation. Courtesy of Hazel Marks. ↩︎

- Arthur Rothstein, Footpaths across the Field Connect the Cabins. Gee’s Bend, Alabama, 1937. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, reproduction number LC-DIG-fsa-8b38853. ↩︎

- Arthur Rothstein, Cabin with Mud Chimney. Gee’s Bend, Alabama, 1937. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, FSA/OWI Collection, reproduction number LC-DIG-fsa-8b35932. ↩︎

Lisa Gail Collins is Professor of Art and Director of American Studies on the Sarah Gibson Blanding Chair at Vassar College. Her books include The Art of History: African American Women Artists Engage the Past and New Thoughts on the Black Arts Movement (coedited with Margo Natalie Crawford).

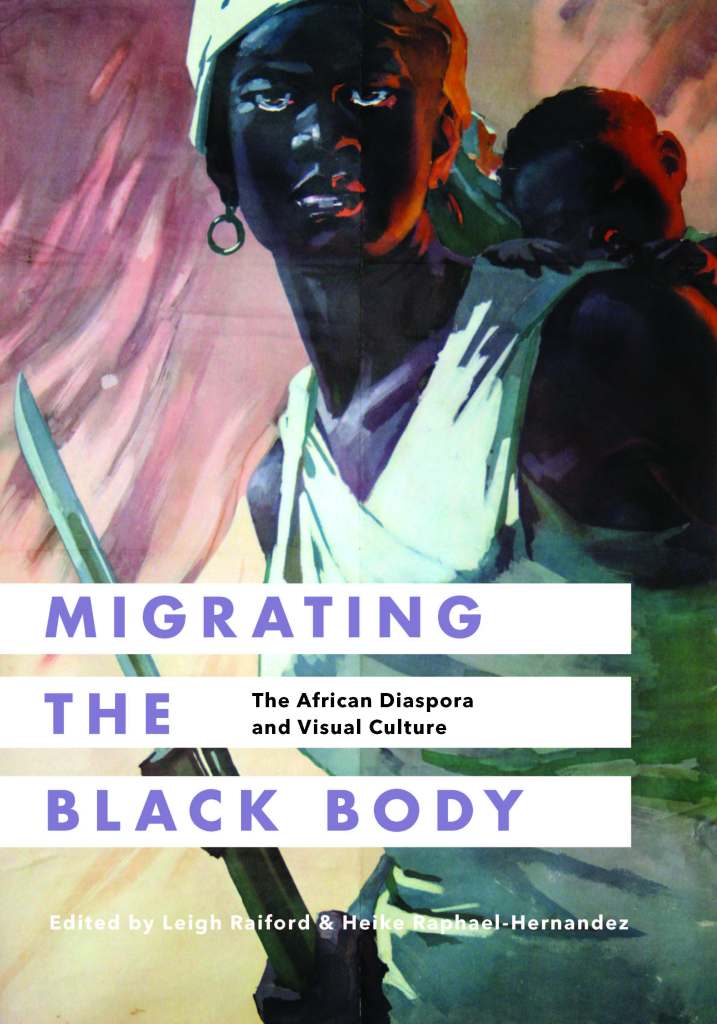

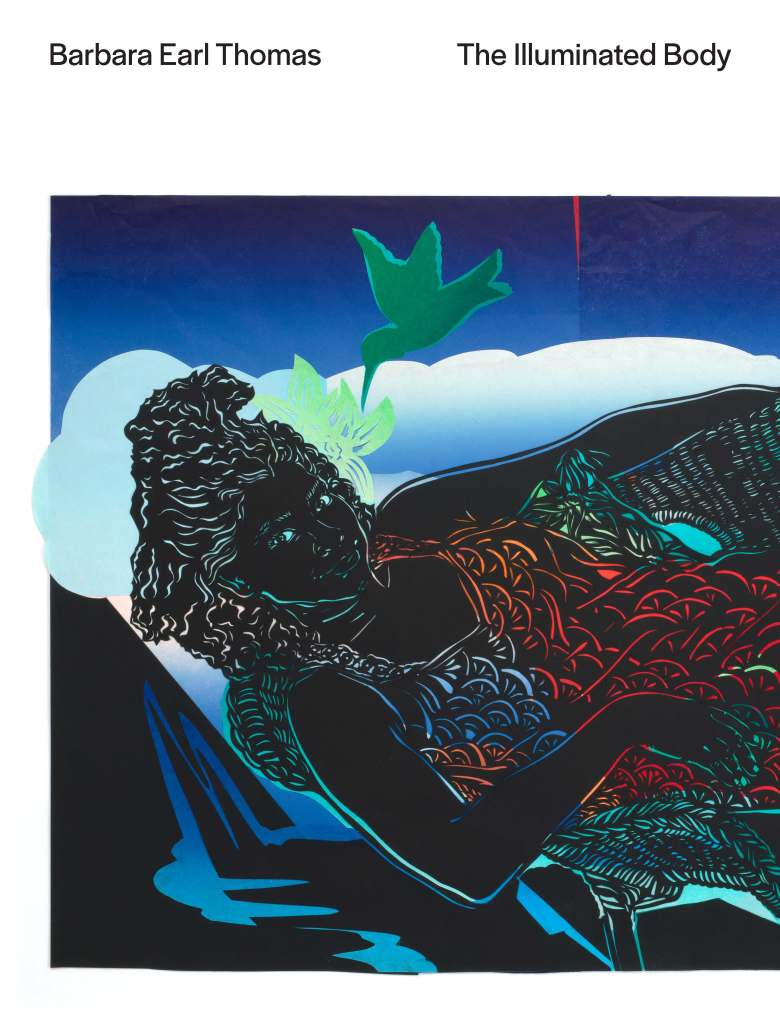

Related Books

nesday, December 7, 2016 marks the 75th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii that thrust the United States into World War II. Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe will visit Pearl Harbor with US president Barack Obama later this month, making Abe the first Japanese leader to visit the site of the attack since 1941 (

nesday, December 7, 2016 marks the 75th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii that thrust the United States into World War II. Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe will visit Pearl Harbor with US president Barack Obama later this month, making Abe the first Japanese leader to visit the site of the attack since 1941 (