-

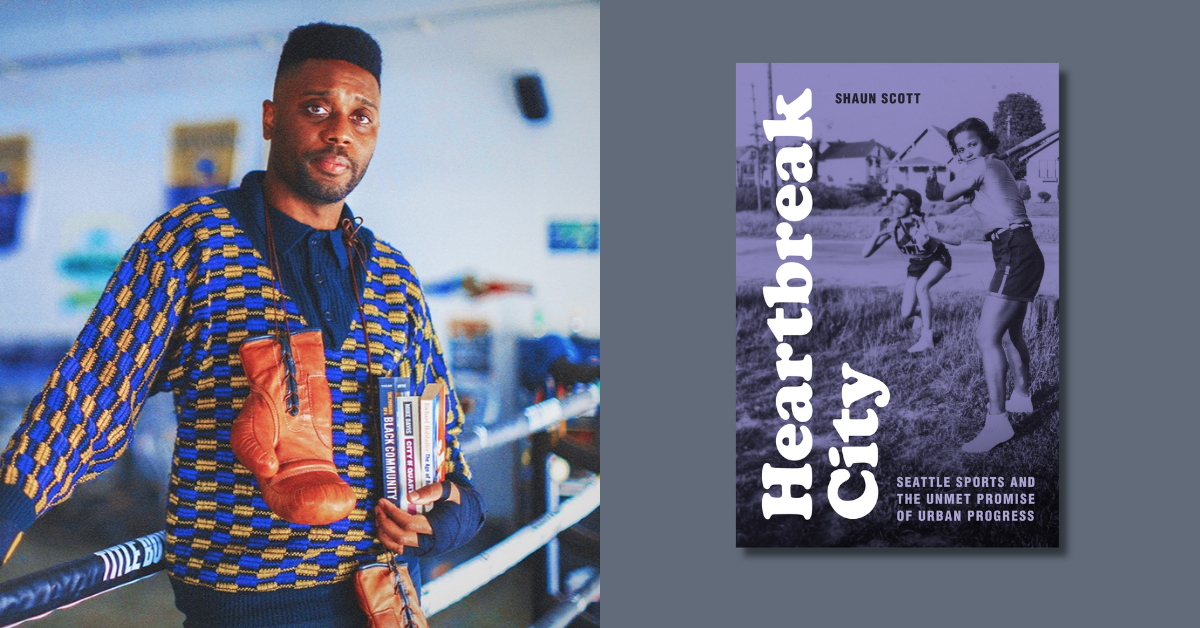

Continue reading →: From “Heartbreak City”: The Story of Seattle’s All-Black Women’s Softball Team

Continue reading →: From “Heartbreak City”: The Story of Seattle’s All-Black Women’s Softball TeamFor Black History Month, we’re sharing an excerpt from Heartbreak City: Seattle Sports and the Unmet Promise of Urban Progress by Shaun Scott on the Seattle Owls. Long before A League of Their Own, this all-Black women’s softball team broke new ground on the diamond as Black Seattleites reshaped the…

-

Continue reading →: Excerpt from “Citizen 13660”: Miné Okubo’s Witness of Incarceration

Continue reading →: Excerpt from “Citizen 13660”: Miné Okubo’s Witness of IncarcerationFirst published in 1946, Citizen 13660 remains one of the earliest and arguably best-known autobiographical accounts of the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Through spare prose and more than 200 drawings, Nisei artist Miné Okubo documented daily life inside the camps. An accomplished artist before the war,…

-

Continue reading →: Compulsory Sexuality and Asexual Possibilities: A Conversation with Kristina Gupta on “Acing Science”

Continue reading →: Compulsory Sexuality and Asexual Possibilities: A Conversation with Kristina Gupta on “Acing Science”Sexual desire is often treated as a given—something everyone has and should have. Compulsory sexuality operates as a largely unexamined premise, shaping not only popular culture but scientific research. In Acing Science: Compulsory Sexuality and Asexual Possibilities, author Kristina Gupta reveals the limits and exclusions of defining desire as universal.…