The University of Washington Press joins the Yakama Nation, Northwest Native tribes, and the many individuals, organizations, and institutions grieving the loss of elder Virginia Beavert, who passed away on February 8 at the age of 102.

Beavert, who was also known by her Yakama name, Tuxámshish, was a noted Native scholar and linguist and a tireless advocate for tribal culture and traditions.

“UW Press is honored to have published three books in collaboration with the legendary and deeply knowledgeable Virginia Beavert,” says press director Nicole Mitchell. “Through these works, her learning and wisdom will continue to reach students in Native communities and beyond for many generations to come.”

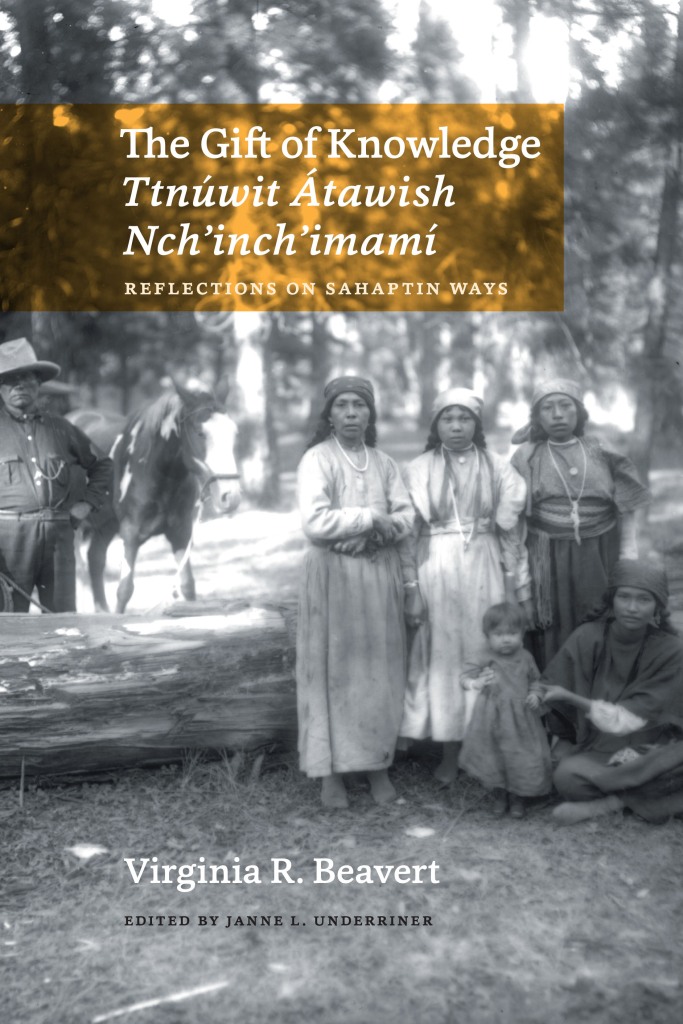

Ichishkíin Sinwit Yakama / Yakima Sahaptin Dictionary, coauthored with Sharon L. Hargus and copublished with Heritage University, is the first published dictionary of any Sahaptin dialect and documents the Ichishkíin dialect spoken by the Yakama people of Eastern Washington. The Gift of Knowledge / Ttnúwit Átawish Nch’inch’imamí: Reflections on Sahaptin Ways, authored by Beavert and edited by Janne L. Underriner, includes cultural teachings, oral history, and stories (many in bilingual Ishishkíin-English format) about family life, religion, ceremonies, food gathering, and other aspects of traditional culture. Anakú Iwachá: Yakama Legends and Stories, coedited with Michelle M. Jacob and Joana W. Jansen, presents stories that Yakama elders recorded in several dialects of the Ichishkíin language that Beavert collected and translated into English.

Below, longtime UW Press executive editor Lorri Hagman reflects on Virginia Beavert and her work.

When I began working with Virginia in 2013 on The Gift of Knowledge, she was, at the age of 92, already a legend in her own time. In 1986, at 65, when most people would have settled into retirement, she earned her bachelor’s degree in anthropology from Central Washington University. That was followed by a master’s degree in bilingual/bicultural education from the University of Arizona in 2000 (at age 79) and a PhD in linguistics from the University of Oregon in 2012 (at age 90). Virginia was still traveling from her home in Wapato, Washington, to the University of Oregon in Eugene to mentor students and teach the Ichishkíin language, and she had published her 560-page dictionary and the first edition of her collected Yakama legends and stories—monumental contributions to scholarship. Now she was eager to transform her doctoral dissertation into a book for general readers, especially future generations of the Yakama Nation. That book, The Gift of Knowledge, narrates stories from Virginia’s own life that exemplify Yakama lifeways and values.

My quintessential Virginia memory is a story she told when we met in Eugene, Oregon, for what turned out to be a leisurely three-hour breakfast. Horses played a big role in her own life, but this horse story is about how her mother, as a child, was stranded alone overnight and was protected by horses from wolves. It is included in The Gift of Knowledge:

My mother had an experience when she was young where horses saved her life in the mountains. She was taking care of them during a berry picking trip to the Trout Lake area. An Elder told her to take the horses to a certain meadow to graze. She was to leave them and walk back to camp. It was already past noontime and she did not question the request. She rode her own horse bareback, and towed the horses together with a rope halter, the head of one horse to the tail of the one in front, and navigated them in that way.

It was getting dark when she reached her destination. She hurried back toward camp but it became so dark she could not see the trail and was forced to get down on her hands and knees and feel her way. Soon she heard the timber wolves at a distance; they came nearer and nearer. She said she began to feel sorry for herself and was thinking that her relatives did not love her; that they wanted her to die. As she was feeling her way along the trail she felt something warm and soft. It was the nostril of her horse, Taḵawaakúɬ, who had come back to rescue her. She took hold of his tail and he led her back to the meadow. The wolves were following them all the way.

In the meadow all the horses gathered around her. Her horse lay down, and she slept on his belly to keep warm until morning. The wolves were not able to reach her because the horses surrounded and protected her. In the morning she went back to camp and no one mentioned anything. No one apologized to her or wanted to know how she had made out. She explained that that was the cultural way. They wanted her to find a spiritual power from the mountains. While she was asleep she acquired that power. She was a healer for women.

Virginia grew up in a traditional, Indian-speaking household. Her maternal grandmother was a shaman, as were her father and mother; her great-great-grandmother was an herbal doctor and midwife. As a child, she was surrounded by people who spoke Nez Perce, Umatilla, Klikatat, and Ichishkíin. Until she went to school at age eight, her life was spent learning about the world around her, along with skills such as food gathering and the use of medicinal plants. Her work on Native languages began at age twelve, when she met linguist Melville Jacobs while she was working with his student, anthropologist Margaret Kendell, as liaison and interpreter for the people Kendell interviewed. When Jacobs discovered that Virginia was a fluent speaker of the Klikatat language, he taught her to read and write the orthography he had developed to record Klikatat stories, and she began a lifetime of work on Native languages.

During World War II, Virginia joined the United States Air Force, serving as a wireless radio operator at the B-29 Bomber Base at Clovis, New Mexico. After the war, she bought herself a thoroughbred horse, which she rode in races and rodeos, and she earned a living as a medical secretary. Her stepfather—a multilingual speaker of Ichishkíin and southern Salish dialects who had worked with University of Oregon linguist Bruce Rigsby to record oral histories and legends—convinced her to return to school and study anthropology.

She went on to teach courses on Native American languages and cultures at Central Washington University; Yakima Valley College; Wapato High School; Heritage University in Toppenish, Washington, on the Yakama Reservation, where she was the director of the Sahaptin Language Program; and the Northwest Indian Language Institute and World Language Academy at the University of Oregon.

Virginia was the first woman elected as secretary-treasurer of the Yakama Nation’s General Council and served on the council from 1974–85. She was a 2006 recipient of the Washington Governor’s Heritage Award; 2007 Central Washington University Alumna of the Year; 2008 recipient of the Ken Hale prize of the Society for the Study of the Indigenous Languages of the Americas; and 2008 recipient of a Distinguished Service Award, University of Oregon.

—Lorri Hagman