Photographs of receding glaciers are one of the most well recognized visualizations of human-caused climate change. These images, captured through repeat photography, have become effective with an unambiguous message: global warming is happening, and it is happening now. But this wasn’t always the case. The meaning and evidentiary value of repeat glacier photography has varied over time, reflecting not only evolving scientific norms but also social, cultural, and political influences.

In Capturing Glaciers, Dani Inkpen historicizes the use of repeat glacier photographs, examining what they show, what they obscure, and how they influence public understanding of nature and climate change. Though convincing as a form of evidence, these images offer a limited and sometimes misleading representation of glaciers themselves. Furthermore, their use threatens to replicate problematic ideas baked into their history.

Excerpt from Capturing Glaciers

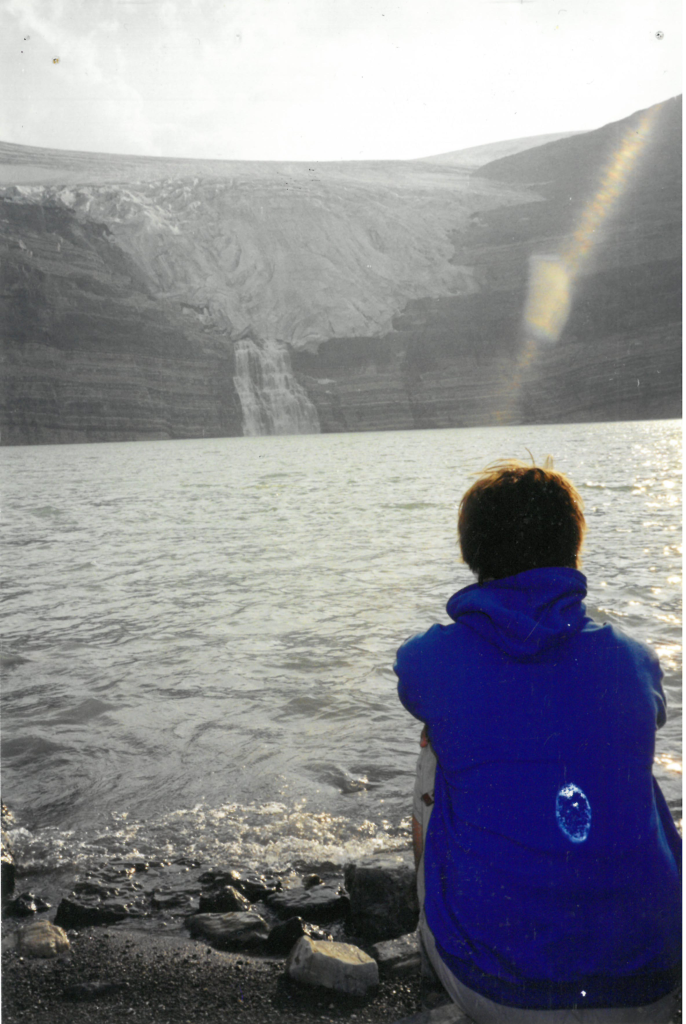

I visited an old friend recently. It had been years since seeing the Bow Glacier. Both of us had changed. I was last in her neighborhood on a winter day so bright and cold it transformed my breath into crystals that shivered and sparkled in the air. She was indisposed, hibernating beneath her billowy robes of winter snow. I had to content myself with a view of her front garden, soft and rounded, blue and white. In summer she presides over one of the most breathtaking scenes on the (for now) aptly named Icefields Parkway in the Canadian Rockies. Perfectly framed by peaks, the glacier perches above the indigo waters of Bow Lake, to which she is connected by thundering Bow Falls and a creek that winds its way through rainbow-pebbled flats. The whole scene can be taken in from the front porch of red-roofed Bow Lake Lodge, set on the lake’s shore by packer and guide Jimmy Simpson. In 1898 he deemed this a good spot to “build a shack.”

I met the Bow Glacier the summer I left home, one of those free-spirited summers that Hollywood films coat thickly with nostalgia. Freshly released from the corridors of teenagedom, I chose a seasonal job that could not possibly advance the career I was preparing for in college but that would give me plenty of time in the mountains: housekeeping at a historic alpine lodge. In my time off I often scrambled up chossy peaks where I met wobbling marmots and grizzlies lounging in full-blooming meadows. I drank from swift, icy streams and camped wherever suited me (because, like many seasonal workers, I believed that national park rules didn’t apply to me). The Bow Glacier looked on with dignified indifference. I stood on her surface, secure in mountaineering harness and crampons (though a couple foolish times not) and marveled at the white westing plains of the Wapta Icefield from which the Bow drains, dreaming of even grander vistas beyond. I knew in those moments I was one of thousands to behold that sight yet felt like the world had just taken form. My happiness was untouchable, not yet complicated by the conundrums of adulthood. I was immortal; death did not exist and time would never run out.

But time does run. And glaciers, compressions of time in frozen water, are excellent gauges of its passage. Mountain glaciers like the Bow are disappearing at rapid—and accelerating—rates. When Jimmy Simpson pondered building his shack, the Bow cascaded down to a forest abutting the lake in three undulating lobes, with the topmost flaring like outstretched eagle wings. I studied its shape from a black-and-white photograph hanging in the lobby of the lodge. Crevasse-torn icefalls separated the lobes, giving the glacier an intimidating look. It was big. It was beautiful. But the Bow Glacier has since receded. When I arrived one hundred years later, only the topmost lobe remained; dark cliff bands, wetted by Bow Falls, stood where crevasses once churned. The eagle wings were gone, and the glacier’s surface was noticeably lowered. Yet you could still see its toe from the lodge. Today it has retracted even further. Like a wounded spider, it now huddles on the lip of the cliff over which it draped in 2003, barely visible from Bow Lake Lodge.

Photographs of glaciers are about more than just glaciers. They’re also about nature, land, how we can know about such things, and the value we ascribe to them. Grasping this allows us to better appreciate repeat glacier photographs for what they can tell us about global warming, but also how they are conditioned by history and where they fall short.

Dani Inkpen

For many people who are not climate scientists, drastic recession of mountain glaciers like the Bow is clear and persuasive evidence of global warming. Since most folks have never been to a glacier, photographs are often how they learn of disappearing ice. This is achieved through what are called repeat photographs: juxtapositions of old photographs and recent re-creations taken from the same perspective at the same time of year (because glaciers fluctuate with the seasons). Curiosity about the historical photographs in repeat series, like the one hanging in Bow Lake Lodge’s lobby, eventually pulled my carefree summer in the Rockies into the trajectory of a professional life.

My book, Capturing Glaciers, is the result: it is about the people who photographed glaciers repeatedly and systematically to produce knowledge about glaciers and a variety of other subjects such as ice ages, wilderness, the physics of ice, and global warming. Throughout the twentieth century those studying glaciers used photography to capture changes in glacier extent and distribution, but they did so for different reasons and with different consequences. I trace the evolving motivations behind the use of cameras to capture images of ice and concomitantly changing ideas about what is (or is not) being captured.

The book title is thus a double entendre, referring to both the enduring allure of glaciers as repeat photographic subjects that “capture” beholders and the variety of ways people sought to capture glaciers with their cameras. I pay especial attention to the perceived value of repeat photographs as a form of evidence. Doing so illuminates some of the ways repeat photography has encapsulated and conveyed changing ideas about what glaciers are and why they matter. Photographs of glaciers are about more than just glaciers. They’re also about nature, land, how we can know about such things, and the value we ascribe to them. Grasping this allows us to better appreciate repeat glacier photographs for what they can tell us about global warming, but also how they are conditioned by history and where they fall short. It helps us see them not as static representations of the present situation, but as still-evolving elements in a process much bigger and more complex than any photograph could possibly capture.

I take a photograph-centered approach, following the photographs to archival information about the practices behind their creation. The history of how repeat photography was used to study glaciers in North America is checkered and discontinuous. Its value as a form of evidence ebbed and flowed based on ideas about what glaciers were and what knowledge-makers wanted to know. This was more than just a scientific matter. While many of the actors who populate the pages of the book were scientists, producing knowledge of glaciers required an extensive host of characters and institutions. And the meanings of repeat glacier photographs broke the bonds of scientific intention and interpretation, drawing from and circling back to potent cultural associations. We will see, then, that the value of a form of evidence is conditioned by nonscientific elements, including political and practical considerations. Evidence, like objectivity, has a history. And history continues to make itself felt in the present.

Dani Inkpen is assistant professor of history at Mount Allison University.

More from the Weyerhaeuser Environmental Books Series