We are delighted to welcome the Association for Asian American Studies and its members to Seattle for AAAS 2024. This year marks fifty years of contributions to Asian American literary history here at the University of Washington Press and whether or not you’re attending the conference, we have lots in store to celebrate, including author talks and readings that are open to all.

Read on for information about upcoming events and new and forthcoming releases, and visit our virtual exhibit to discover more notable books in Asian American studies. We are pleased to offer AAAS members a 30% discount on all orders to US addresses with promo code WAAAS24 at checkout on our website through May 31, 2024.

New & Forthcoming Books

Island X: Taiwanese Student Migrants, Campus Spies, and Cold War Activism by Wendy Cheng

Public author talk on April 24, 3:30–5:00 pm

“A fascinating, lively account of the Taiwanese diaspora’s surprising influence on America—and America’s furtive investment in their fates, as well.”

—Hua Hsu, author of Stay True: A Memoir

Transpacific, Undisciplined ed. by Lily Wong, Christopher B. Patterson and Chien-ting Lin

AAAS panel on April 25, 10:00–11:30 am

“This superb collection deepens and necessarily challenges our understanding of the ’transpacific.’”

—Crystal Mun-Hye Baik, author of Reencounters: On the Korean War and Diasporic Memory Critique

Dancer Dawkins and the California Kid by Willyce Kim

Public event on April 26, 7:00–8:30 pm

AAAS panel: The Legacies of Aiiieeeee! on April 27, 1:00–2:30 pm

The newest release in the Classics of Asian American Literature series, “Willyce Kim’s groundbreaking debut novel . . . returns to us now in this beautiful new edition, a new home to these iconoclastic rebel lesbians, giving back to us a much-needed queer classic“ (Alexander Chee, author of How to Write an Autobiographical Novel).

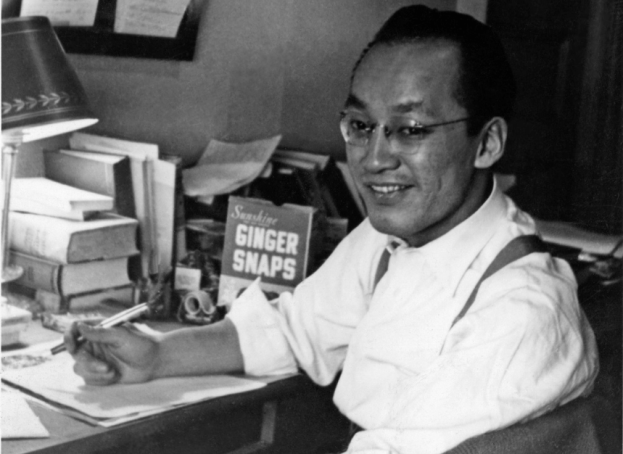

The Unknown Great: Stories of Japanese Americans at the Margins of History by Greg Robinson with Jonathan van Harmelen

Public author talk on April 25, 6:00 pm

AAAS Roundtable in Honor of Roger Daniels on April 26, 1:00–2:30 pm

“Greg Robinson is the foremost chronicler of not only the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, but also an eminent historian of the life of the community before and after. With a depth of research unlikely to be rivaled . . . he [offers] a glimpse into the fullness of humanity that otherwise would be obscured or forgotten.“

—Frank H. Wu, coauthor of The Good Citizen

Exiled to Motown: A Community History of Japanese Americans in Detroit by Detroit JACL History Project Committee

Drawing from a community-based oral history and archiving project, Exiled to Motown captures the compelling stories of Japanese Americans in the Midwest, filling in overlooked aspects of the Asian American experience.

Resisting the Nuclear: Art and Activism across the Pacific ed. by Elyssa Faison and Alison Fields

“Essential reading—informative, insightful, revealing, and timely. An important invitation to remember lives lost and impacted by nuclear disasters and to pause and review the ways nuclear power has been mobilized in relation to US imperialism and racial-settler capitalism.” —Susette Min, author of Unnamable: The Ends of Asian American Art

Upcoming Public Events

- Island X: Taiwanese Student Migrants, Campus Spies, and Cold War Activism Author Talk

Wednesday, April 24, 3:30 pm at UW, Thomson Hall Room 317

Drawing on interviews with student activists and extensive archival research, Wendy Cheng documents how Taiwanese Americans developed tight-knit social networks as infrastructures for identity formation, consciousness development, and anticolonial activism. This free event will be held in person and streamed online. For more information and to register, visit the event page here.

- The Unknown Great: Stories of Japanese Americans at the Margins of History Author Talk

Thursday, April 25, 6:00 pm at Densho

Through stories of remarkable people in Japanese American history, The Unknown Great illuminates the diversity of the Nikkei experience from the turn of the twentieth century to the present day. Acclaimed historian and journalist Greg Robinson, along with his collaborator Jonathan van Harmeen, examines the longstanding interactions between African Americans and Japanese Americans, the history of LGBTQ+ Japanese Americans, mixed-race performers and political figures, and much more. Robinson and van Harmelen will be joined in conversation with Nina Wallace, Densho Media and Outreach Manager, as they shine a spotlight on lesser-known stories and unheralded figures from Japanese American history.

This event will be held in person at Densho and is free to attend, but registration is required as there will be limited seating. For more information and to register, visit the event page here.

- 50 Years of Asian American Literary History at the University of Washington Press

Friday, April 26, 7:00 pm at the Seattle Public Library, Central Library

From the seminal anthology Aiiieeeee! and Carlos Bulosan’s America Is in the Heart to the most recent publication, Willyce Kim’s Dancer Dawkins and the California Kid, join us for a celebration of the UW Press’ contribution to Asian American literature in bringing classic works back into print and championing new writing. Hosted by Shawn Wong and featuring readings from Willyce Kim, Ching-In Chen, and Yanyi, with a Q&A moderated by Eunsong Kim. Books will be available from Elliott Bay Book Company.

This event is free, and registration is not required.

Read More on the Blog

Behind the Covers: Author Greg Robinson on The Unknown Great