Campy and competitive, gay rodeo offers a community of refuge that straddles the urban and rural, providing space to both embrace and challenge the idealized masculinity associated with the iconic cowboy of the US West.

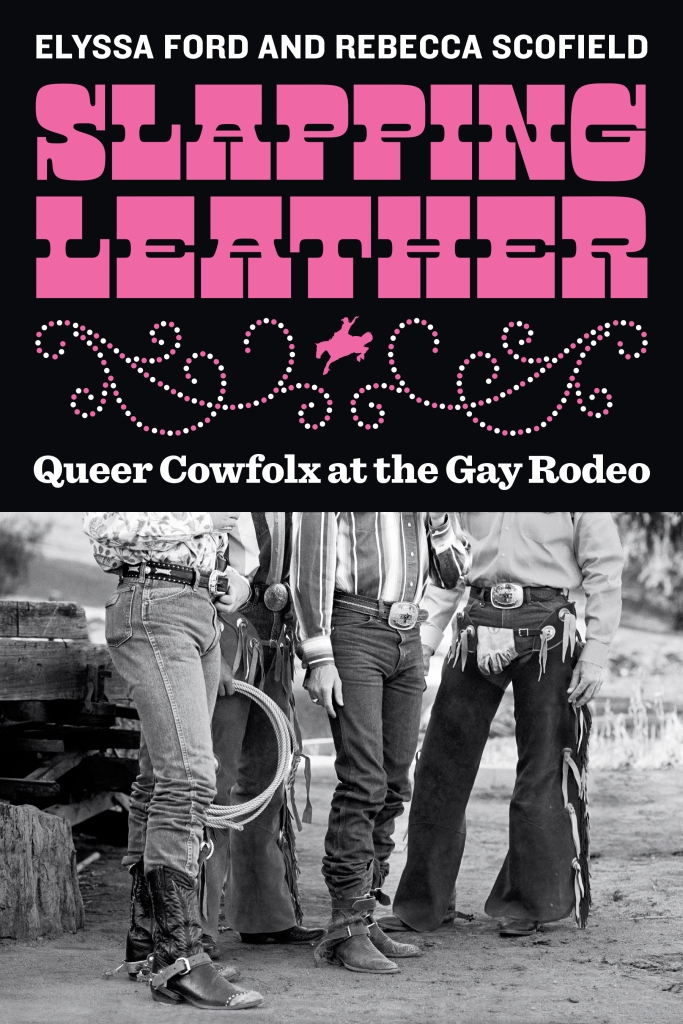

Slapping Leather: Queer Cowfolx at the Gay Rodeo brings together over a decade of research by Elyssa Ford and Rebecca Scofield, historians of gender and sexuality in the American West. The book explores the complex history of gay rodeo from the late 1960s through the 2010s as a case study for western cultural performance, LGBTQ+ community building, queer philanthropy, and the creation of a racialized and gendered image of the queer cowboy.

As part of the American Historical Association annual meeting, taking place in San Francisco from January 4 to 7, we are pleased to offer AHA members a 30% discount. Find Slapping Leather and other new and notable books through our virtual booth and take advantage of the conference discount with promo code WAHA24 at checkout through February 15, 2024.

To start, can you share about your scholarly backgrounds and what led you to gay rodeo?

Ford: My senior year in college, I decided to explore my interest in museums and completed an internship at the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame in Texas. The very limited racial diversity of the museum in the early 2000s made me ask questions about women, race, and rodeo in the US, and those are themes I studied in both my MA and PhD. I came across gay rodeo at that time, but it didn’t fit into the scope of my work until my first book, Rodeo as Refuge, Rodeo as Rebellion: Gender, Race, and Identity in the American Rodeo (University Press of Kansas, 2020), when I included a chapter on that rodeo circuit.

Scofield: While completing a master’s degree in Regional Studies: East Asia, I was in Tokyo looking at the acrylic nail industry when I saw a store called Rodeo Clowns, which was selling cowgirl boots to Japanese teenagers. It completely changed my academic trajectory, and I began researching the rise of western wear and looking at how the “cowboy” became a straight white man when so many people outside that limited definition were participating in country western culture. As a part of this, my first book, Outriders: Rodeo at the Fringes of the American West (University of Washington Press, 2019), included a chapter on gay rodeo.

There was so much more to examine in gay rodeo than we were able to tackle in just our single chapters. Rather than pursuing separate book projects, we decided to work together so we could combine our decade worth of research and bring our overlapping—but also different—areas of interest within gay rodeo into a single volume.

Many queer cowfolx narrate finding the rodeo as a moment of finding community. They had been convinced they were the only gay person who loved country music, riding horses, or line dancing. The ability to do the sport they loved in a safe space was revolutionary.

Elyssa Ford and Rebecca Scofield

In writing the book, you drew on multiple archives and over seventy oral interviews. Can you share more about your process and how the book took shape?

Co-authorship is not particularly common in the field of history, and neither of us had approached a project in this way before. And we had never met. In fact, we never met in person until the book was finished! However, the changes to digital communication during COVID really worked to our advantage, with Zoom and Google Docs allowing us to collaborate, communicate, and share materials. We already had conducted much of the necessary research and interviews during our first book projects, and we both knew the material so well that we quickly identified the chapters we wanted to include. We also were lucky that our specific interests within gay rodeo combined in such a way that we each developed several chapters individually and then worked collaboratively on others.

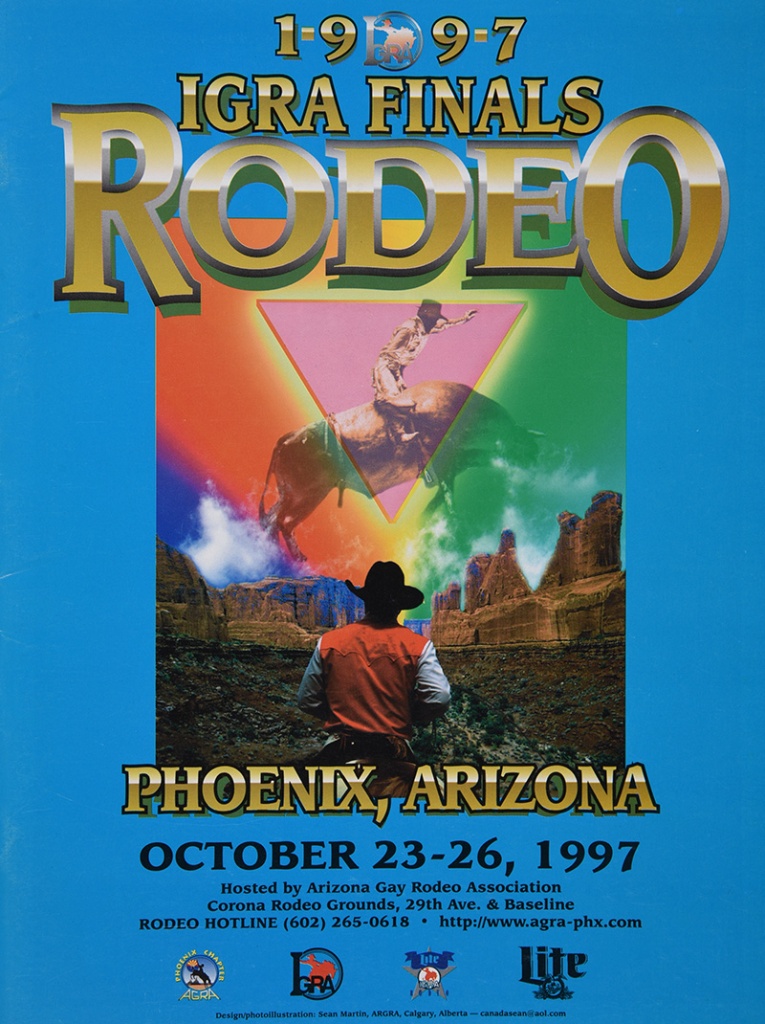

The archival materials and oral interviews were such an integral part of this project. We revisited the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles to complete a comprehensive examination of their International Gay Rodeo Association (IGRA) collection, and we continued to conduct interviews with participants as part of the Gay Rodeo Oral History Project. Both added new dimensions to our chapters and helped us tell a more complete story about the complexity of gay rodeo’s origins and evolution.

You write that “as rodeo professionalized, it also narrowed the boundaries of the cowboy.” Can you elaborate on this and the effect it had on gay rodeo in its nascency?

Phil Ragsdale, and later the IGRA, initially created gay rodeo as a fundraising event and as a place for queer cowfolx to compete in rodeo. Yet it also was rooted in a hegemonic masculinity so that gay cowboys in particular could adopt, demonstrate, and exert the traditional white masculinity of the American cowboy of western mythology. This vision for gay rodeo clashed with the presence of lesbians, drag queens, and camp events, and while some participants fought for those elements, others pursued a rodeo modeled on the professional rodeo circuit. As gay rodeo struggled in the 1990s for legitimacy in the straight rodeo world, it became increasingly difficult to find space for the elements of gay rodeo that failed to fit into the dominant rodeo narrative.

Gender, politics, and geography all play into the history of gay rodeo, which you call a “case study for belonging.” Can you share more about community-building within the sport and a few examples of the tensions LGBTQ+ people faced both within and outside of the gay rodeo arena?

Many queer cowfolx narrate finding the rodeo as a moment of finding community. They had been convinced they were the only gay person who loved country music, riding horses, or line dancing. The ability to do the sport they loved in a safe space was revolutionary. However, it also came with a lot of negotiation as all the assumptions of what it meant to be a cowboy still played out in gay rodeo, often with drag queens and lesbians being made to feel less welcome at times.

Additionally, gay rodeo emerged at a time when the mainstream LGBTQ+ movement was gaining steam but came of age in the shadow of the AIDS epidemic. So the organization always had to balance the desire to be visible with an increasingly hostile public who could use AIDS as a reason for hate. Gay rodeos have been protested by religious groups, animal-rights groups, and many others. This brought gay rodeoers together to support their own efforts and also saw them combine forces with other LGBTQ+ organizations for AIDS fundraising and Pride events, and other rodeo groups, to counter animal-rights protests.

Between chapters, stories from gay rodeo participants are included as oral history vignettes. Why did you choose this type of framing?

It was important to us to share how real people expressed their gratitude and love for this space and illustrate that while we are taking an academic approach, this is a living, thriving community that allowed us access to their stories.

What does the future of gay rodeo look like?

That is the $100 question! And, it is the question that keeps many in gay rodeo awake at night. Gay rodeo is at a crossroads today as it attempts to overcome the serious impact of COVID, a changing and more welcoming society for queer people, and the lack of a single unifying force, such as AIDS or extreme homophobia. As we discuss in our final chapter, IGRA today is grappling with these questions and looking for ways to reach new groups of participants and new audiences.

What do you hope readers take away from the book?

This is a group of people who never easily fit into society’s assumptions about politics, geography, or culture. We hope this helps people rethink with more nuance who belongs where.

Elyssa Ford is associate professor of history at Northwest Missouri State University and author of Rodeo as Refuge, Rodeo as Rebellion: Gender, Race, and Identity in the American Rodeo. Rebecca Scofield is associate professor of American history at the University of Idaho and author of Outriders: Rodeo at the Fringes of the American West.

Related Books

New & Forthcoming in History