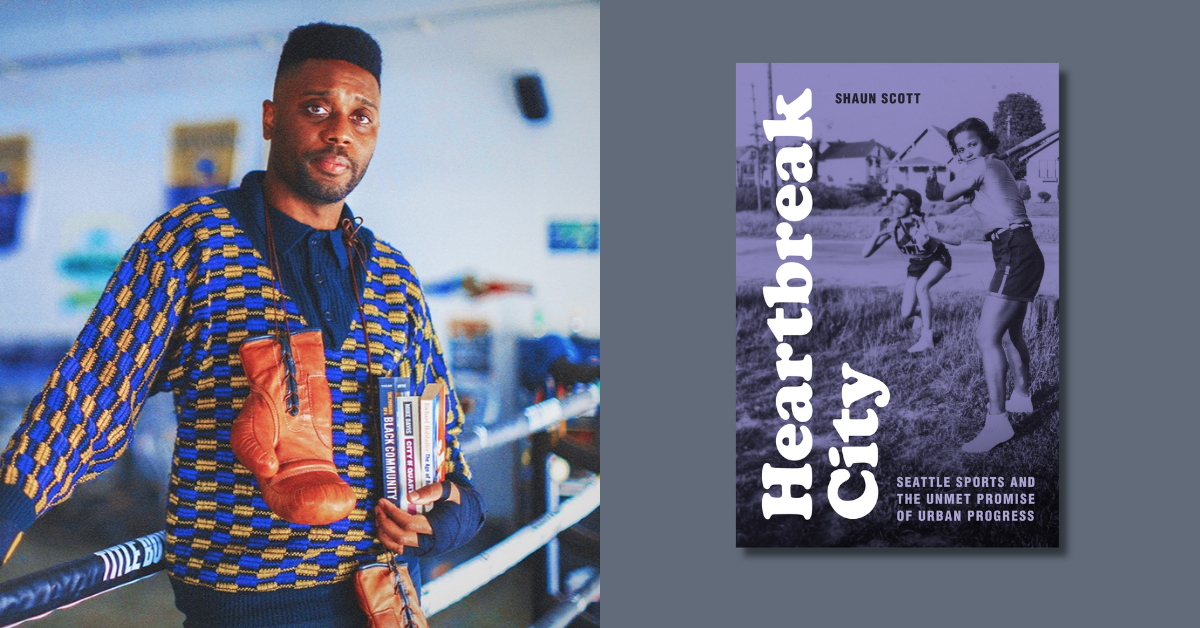

For Black History Month, we’re sharing an excerpt from Heartbreak City: Seattle Sports and the Unmet Promise of Urban Progress by Shaun Scott on the Seattle Owls. Long before A League of Their Own, this all-Black women’s softball team broke new ground on the diamond as Black Seattleites reshaped the city’s workforce.

Historian John C. Putnam relays that at the turn of the century, “women participated in nearly a dozen unions, including locals for beer-bottlers, telephone operators, cigarmakers.”1 In 1914 the Seattle Police Department “hired” unpaid Black Seattle woman Corinne Carter. On the force she rescued Black domestic servant girls living in slavery-like conditions in Seattle and later established a YWCA chapter that offered Central Area physical fitness facilities for “Negro Health Week” in 1947.2 For Seattle women seeking full entry into American life, sports were an important proving ground.

Black women in Seattle were the future, their position within the city’s social hierarchy forecasting labor conditions and strategies of resilience replicated by others many years later. For the broader society, the flight of men from households, workplaces, and positions of power in service of World War II created new opportunities; as the rate of employment for Seattle women increased 57 percent between 1941 and 1946, the national divorce rate doubled.3 Women worked as mechanics and machinists, embodying the Rosie the Riveter iconography that illustrated their worth to the wartime economy.

Chewing gum tycoon Philip K. Wrigley capitalized on ascendant American women when he created the All-American Girls Professional Baseball League (AAGPBL) in 1943. Later immortalized in the film A League of Their Own, this all-white story of economic empowerment leading to sports triumph traced a template trod earlier by Black Seattle women.

In the Seattle Owls baseball team, the triple pressures of race, class, and gender adversity had created diamonds.

With a roster composed entirely of Black women, the Seattle Owls baseball team played its home games at Sick’s Stadium in the 1930s, won the Washington State Softball Championship in 1938, and captured the 1939 city championship. In the process they reproduced the grit of Seattle Black women who served as the backbone of their beleaguered community.

As America recovered from the Great Depression in the late 1930s, the Black unemployment rate in Seattle (24.3 percent) was second only to Milwaukee; because the downturn hit Black men in Seattle particularly hard, Black women entered the labor force to support themselves and their social networks, finding employment as domestic servants and service workers.4 Working for a living produced a hard-won confidence. Photographs of the self-assured Seattle Owls squad depict a team of tight-knit competitors, bandaged by the baseball hustle but still debonair enough to don hoop earrings with caps and jerseys—an ahead-of-its-time sartorial play later copied by postindustrial women of all races. In the Seattle Owls baseball team, the triple pressures of race, class, and gender adversity had created diamonds.

After the Owls dismantled a white women’s Bremerton team 21–1 to clinch the 1938 title, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer dubbed them the “Brown Bombers,” spotlighting their “powerful batting attack and smooth-working defense.” Before long, Black women’s labor bolstered the American defense establishment.5 Of the 329 Black workers employed by Boeing at its plants in Seattle and Wichita during World War II, 280 of them were women.6 These “Black Rosies” integrated Boeing in Seattle, simultaneously advancing race and gender progress domestically while aiding the fight against authoritarianism abroad.7 In factories and on the field of play, the presence of fewer white men facilitated the creation of a more fair city.

Washington State Rep. Shaun Scott is a Seattle-based writer and organizer. He is author of Millennials and the Moments That Made Us: A Cultural History of the U.S. from 1982–Present.

Further Reading in African American History

Notes

- John C. Putman, Class and Gender Politics in Progressive-Era Seattle (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2008), 75. ↩︎

- “Negro Woman on Seattle’s Force,” Seattle Times, January 21, 1914, 7; “Program for Negro Health Week Planned,” Seattle Daily Times, March 22, 1947, 3. ↩︎

- “Women, Labor, and World War II,” Oregon Encyclopedia, https://tinyurl.com/472kkesr (accessed June 24, 2022). Statistics about divorce rate taken from “100 Years of Marriage and Divorce Statistics, United States, 1867–1967,” provided by the National Vital Statistics System, taken from Jennifer Betts, “Historical Divorce Rate Statistics,” July 10, 2018, https://tinyurl.com/55zcyhnm. ↩︎

- Quintard Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1994), 69–73. ↩︎

- “Doghouse Team Blows Up in Ninth,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 29, 1938, 11; “Pacific Play in Spokane Tonight,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 29, 1939, 15. ↩︎

- Taylor, Forging of a Black Community, 164–65. ↩︎

- Anne Stych, “‘Josie the Riveter,’ Who Helped Integrate Boeing during World War II, Dies,” Chicago Business Journal, December 19, 2016, https://tinyurl.com/2n3zs6k7. ↩︎